The landscape of higher education in India is the largest in the world, and it signifies the country’s quest for human resource development and the dissemination of knowledge. As per the most recent figures of University Grants Commission (UGC) and All India Survey on Higher Education (AISHE) 2023 reports, India possesses over 1,150 universities, ranging from central and state to deemed and private universities. All types of universities, whether government-funded or private, play an important and complementary role in providing higher education to the nation. The two major categories of Indian universities are government universities, which include central and state universities, and private universities, such as deemed-to-be universities that have been formed by private trusts or societies. Being aware of their categories and functions serves to give a clear indication of how Indian higher education is organized, accessed, and availed.

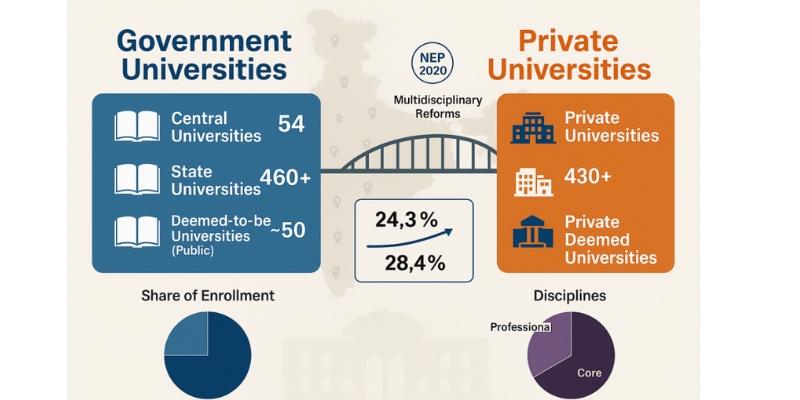

Government universities consist of central universities (established by Parliament Acts and funded by the Union Government), state universities (established by State Legislature Acts and funded by the state governments), and deemed-to-be universities (which may be public as well as private but are granted the status of ‘deemed’ universities by the UGC in accordance with Section 3 of the UGC Act, 1956). There are 54 central universities, more than 460 state universities, and roughly 125 deemed universities as of 2023. They have long been the pillars of India’s public higher education system. Central universities like Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), University of Delhi (DU), Banaras Hindu University (BHU), and Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) have for long been known for their quality, diversity, and national presence. They are the premier research, inter-disciplinary, and nation-building institutions. Likewise, state universities like Osmania University, University of Mumbai, and University of Madras provide regional educational needs with a vast range of undergraduate, postgraduate, and doctoral programs. These universities make significant contributions in providing equal access to education through regional languages and rural areas and thus contributing towards rising in the Gross Enrollment Ratio (GER).

Private universities and private deemed-to-be universities have expanded in thousands over the last two decades in response to the increasing demand for higher education. There are more than 430 private universities and more than 110 private deemed-to-be universities in India, as per AISHE 2023 report. The widespread proliferation of private institutions is accompanied by the liberalization of the Indian economy during the 1990s and the resultant increase in the level of middle-class aspirations. Amity University, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, VIT (Vellore Institute of Technology), and Shiv Nadar University are some of the private universities that have established reputations based on industry-integrated curriculum, international-level facilities, and employability orientation. Such organizations have a tendency to offer new courses in new-generation subjects like Artificial Intelligence, Data Science, Cybersecurity, and Design Thinking. Private universities are found mostly in urban and semi-urban areas and serve students who are in a position to pay for high-quality education and international exposure, internship, and industry interaction.

Private and public universities both are key players in India’s higher education sector regardless of the disparity in finance and management. Government universities are comparatively cheaper and come with more of the rural and economically weaker section. They tend to be the first preference among students sitting for competitive entry exams like JEE, NEET, or CUET. For example, Delhi University receives over a million applications a year for only a few seats in undergraduates, an indication of the faith placed by students in public universities. Private universities, anyway, plugged this gap of demand and supply. They admit approximately 36% of the entire university students in the nation and offer curriculum flexibility, global faculty involvement, double degrees, and cross-disciplinary studies — aspects that are gradually being taken up by state universities as well under the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020.

The NEP 2020 also eroded the crisp differences between government-run and private institutions by promoting autonomy, innovation, and output-oriented education for all. In NEP, institutions are nudged towards being multidisciplinary by 2040, and categorization into research-led universities, teaching-led universities, and autonomous colleges is shared by both government and private institutions. This policy change is to promote excellence, equity, and inclusion in higher education. Already, a few of the private universities like Ashoka University, O.P. Jindal Global University, and Azim Premji University have adopted NEP guidelines by incorporating a liberal arts and interdisciplinary course. Equally, government institutions like IIT Madras and BHU have initiated programs like online degree courses, international collaborations, and innovation centres.

Statistically, GER in higher education has risen from 24.3% in 2014 to 28.4% in 2023, and this rise has been largely driven by the spread of private universities and expansion of government initiatives like RUSA (Rashtriya Uchchatar Shiksha Abhiyan), PM-USHA (PM-URHES for Holistic Advancement), and Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and OBC scholarship students. While private universities currently represent about 39% of the total university institutions, they still hold only about 28% of the enrolled students with a more focused ratio in professional courses including Engineering, Management, Law, and Health Sciences. On the contrary, government universities accept a higher ratio of core disciplines like Humanities, Natural Sciences, Social Sciences, and Education, hence ensuring scholastic diversity and research depth essential for long-term national development.

The quest for quality assurance and accreditation continues to be central to both the systems. Although public universities are predominantly accredited by NAAC with ‘A’ or ‘B’ grades, more and more private colleges are attempting international accreditations like AACSB, ABET, and QS Rankings to raise their global standing. Private university growth in Haryana, Gujarat, and Karnataka states has contributed to regional economic growth, skill enhancement, and employment generation. Conversely, affordability, equity, and commercialization of education in private universities have been the areas of concern, and the UGC has made it obligatory for all the institutions to disclose fees and grievance redressal mechanisms.

Overall, India’s post-secondary education features an interactive co-existence between government and private universities having overlapping but divergent mandates. As state institutions remain committed to ideals of access, equity, and integration, the capacity building, innovation, and internationalization are further enhanced by the private universities. They together have more than 40 million students on their rolls and are the corner stone of India’s vision to build a knowledge economy. Policy change, regulatory control, and collaborative mechanisms render the future of Indian higher education rosy, inclusive, and competitive at a global level.

Prepared by Ch.Sandeep Associate Professor, School of CS&AI, SR University, Warangal, Telangana 506371 ch.sandeep@sru.edu.in