By Dr. P. Praveen, Associate Professor, Department of CSE, SR University, Warangal, Telangana

India’s agricultural economy is the cornerstone of its development, with over 60% of the population directly or indirectly dependent on agriculture. A majority of this vast sector hinges on a single critical resource—river water. From the snow-fed Ganga in the north to the peninsular rivers like the Godavari, Krishna, and Cauvery, these river systems have nourished India’s fertile plains and supported food security for centuries.

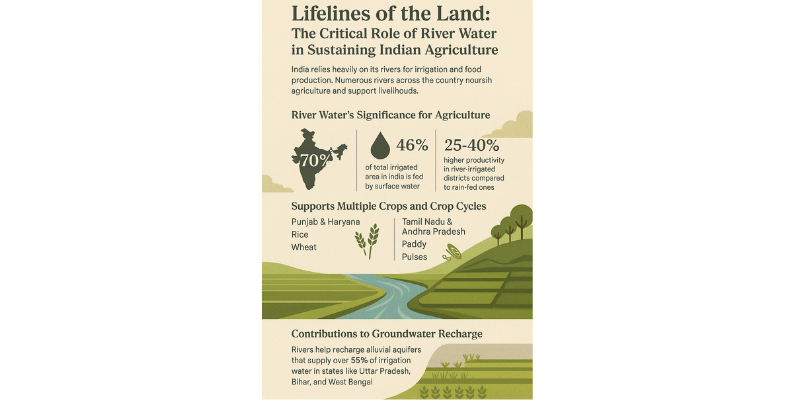

According to the Ministry of Agriculture, about 70% of surface water irrigation comes from river-fed systems including canals and reservoirs. Regions like the Indo-Gangetic Plain, irrigated by rivers such as the Yamuna and Ganga, are among the world’s most fertile and productive.

Major irrigation projects like Bhakra-Nangal (Sutlej), Tungabhadra (Krishna), and the Indira Gandhi Canal (Sutlej and Beas) have transformed arid lands into productive agricultural belts. Data from the Command Area Development Programme confirms that river-irrigated areas produce 2 to 3 times more yield than rain-fed regions. Rivers also allow for multiple cropping cycles, such as rice and wheat rotation in Punjab and Haryana.

Rivers also play an indirect yet essential role in recharging groundwater aquifers, especially in states like West Bengal, Bihar, and Uttar Pradesh, where over 55% of irrigation comes from wells and tube wells. Seasonal floods, though often destructive, contribute rich alluvial silt that enhances soil fertility and helps replenish groundwater.

Yet, this lifeline is under threat. Climate change, over-extraction, and pollution are disrupting the reliability of river systems. UNESCO’s 2022 report warned that glacial-fed rivers could lose up to 30% of their volume by 2050. Pollution from untreated sewage and industrial waste has also rendered rivers like the Yamuna increasingly toxic for irrigation.

Further complications arise from interstate water disputes, such as the prolonged Cauvery conflict between Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. These disputes disrupt irrigation cycles, sowing schedules, and ultimately the livelihoods of farmers.

There are lessons to be learned—from Rajasthan’s success with the Indira Gandhi Canal to Punjab’s cautionary tale of waterlogging and soil salinity due to excessive irrigation.

What Can Be Done?

India needs multi-pronged interventions to sustain its river-fed agriculture:

-

River Interlinking Projects (e.g., Ken-Betwa) to divert water from surplus to deficit areas.

-

Efficient Irrigation Techniques like drip and sprinkler systems under PM Krishi Sinchayee Yojana.

-

Participatory River Basin Management involving farmers and local stakeholders.

-

Restoration of Traditional Water Systems such as tanks, check dams, and stepwells to capture seasonal floods and maintain aquifer levels.

-

Farmer Education on water budgeting, less water-intensive crops (like millets), and sustainable agricultural practices.

-

Grassroots Programs like Pani Panchayats and Participatory Irrigation Management (PIM) for equitable distribution and accountability.

Conclusion

River water is not merely a natural resource—it is the epicenter of India’s agricultural sustainability. As pressures from population growth, climate change, and industrial expansion increase, India must prioritize the preservation, smart use, and governance of its river systems. A future-ready agricultural policy must begin at the river’s source.